You sleep beneath a throbbing blanket,

A whining drone that cuts through the night

Like a monotonous call to prayer;

Serrated sounds that test the edges

Of your chemically-reinforced cocoon.

Draped in treated fabric you drift restlessly;

Your dreams a kaleidoscope of apprehensions,

Where walls run red with shattered husks,

Their swollen bellies gorged on speedballs

Of honeydew, blood, and DDT.

In the morning you check your cotton cage for holes,

Shifting silently beneath the sheets

As you perform these daylight inspections

Like a hushed and fading holy rite.

Creeping from beneath your net

You throw open the door and sunlight cuts

Thorough the residual creases of night.

A breath of cool air that casts out the shadows

Forcing them onto the streets,

Where they wait for you to pass.

This poem is inspired by recent research which has shown that across Africa a higher percentage of mosquito bites than previously thought take place at times when people are not protected by nets and insecticide.

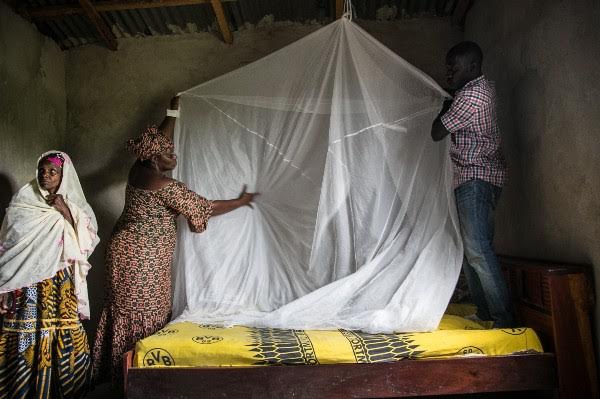

Effective malaria control initiatives, such as the use of treated mosquito nets and indoor residual spraying (the application of insecticide to the inside of dwellings) has proven immensely effective, with an estimated 663 million clinical cases predicted to have been averted from 2000 to 2015. However, despite the massive reductions over recent years, low level transmission persists even where there is universal coverage of treated nets or maximal coverage of indoor residual spraying. This remaining, low level transmission has been termed ‘residual malaria transmission’.

This new research has found that across Africa residual malaria transmission may be much higher than previously thought, and that on average only 79% of bites occur during the time when people are in bed (and thus protected by nets). This value is about 10% lower than previous estimates, suggesting that across Africa an estimated 10.6 million additional malaria cases will occur annually even if the universal usage of treated mosquito nets and indoor residual spraying coverage is achieved. This research suggests that while nets and domestic insecticide will remain key interventions in the battle against malaria, in some locations they will need to be supplemented by approaches that target mosquitos outside of the home.

An audio version of this poem can be heard here:

Discover more from The Poetry of Science

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.