Not all heat is made equal.

Between streets stained

red with the indelible ink

of discrimination,

the clammy embrace

of federal excess

can still be felt.

Microclimates persist as

green gentrification

plasters over the excesses

of historic housing policies,

pacifying those who can

now afford it

with promises of

shaded sycamores and

miniature boating lakes.

Redlines don’t fade, they just

coalesce into stripes –

their bulging contours falling

outside the peripheral vision

of the purposefully blind.

This poem is inspired by recent research, which has found that historical housing disparities in the United States are linked with dangerous climate impacts.

Recent research has shown that extreme heat kills more people in the United States than any other type of hazardous weather, and that this is likely to become even more pronounced in the coming years because of climate change. However, extreme heat does not affect all people equally, as surface temperatures can vary across the different neighbourhoods within a single city by up to 10°C, with many vulnerable communities disproportionately exposed to extreme heat. In this new study, researchers investigated the extent to which historic housing policies, specifically ‘redlining’, have resulted in this disparity.

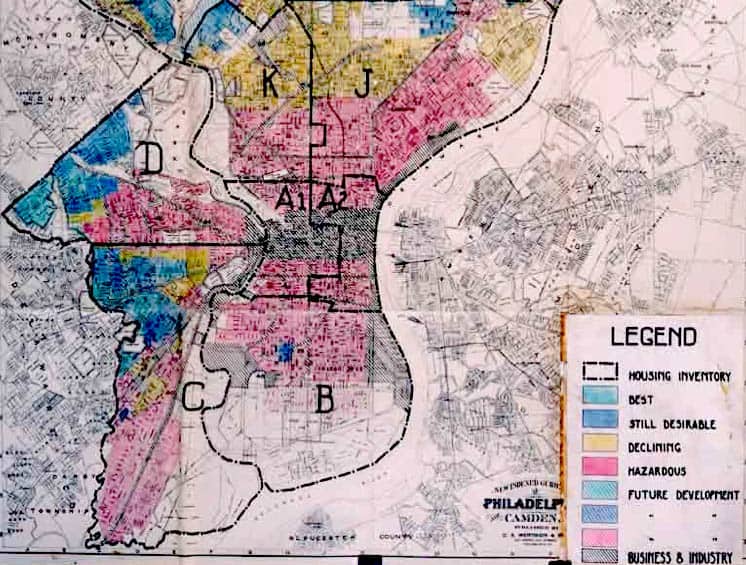

Beginning in the 1930s, discriminatory housing policies in the United States classified some neighbourhoods as being too hazardous for investment, outlining these areas in red on ‘residential security’ maps, and denying residents in these ‘redlined’ neighbourhoods services ranging from banking and insurance to healthcare and supermarkets. While the practice of redlining was banned in 1968, these areas continue to be predominantly home to lower-income communities and communities of colour. By using satellite data and historic housing records for 108 cities across the United States, this study found that in 94% of cases, formerly redlined neighbourhoods were hotter than all other neighbourhoods in that city, being on average 2.6 °C warmer than non-redlined neighbourhoods. This study therefore suggests that as climate change brings heatwaves of greater intensity and frequency, it is the same historically underserved and discriminated neighbourhoods that will ultimately face the greatest impact.

An audio version of this poem can be heard here:

Discover more from The Poetry of Science

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.