In a change to the usual format of this blog, this post features a longform interview with the poet and scholar Donald Beagle, whose recent collection Driving into the Dreamtime was released earlier this year, and is a masterful exploration into the liminal spaces between science and poetry. Donald is a long-time proponent of the complementary nature of science and poetry, and in this interview, he outlines some of his inspiration, his collaborations with the late Radcliffe Squires, and his hopes for an emerging school of science and poetry. His literary awards include the Hopwood Award (University of Michigan), the John Brubaker Award, two prize-winning poems in the annual Ekphrasis Contest (2013 & 2017) and the Gail O’Day Award for Outstanding Achievement in Poetry (Wake Forest University). His work has also recently been selected for the 2021 edition of the “Poetry in Plain Sight” Project, which integrates poems with urban streetscapes through posters in storefront windows in participating cities across North Carolina.

What is your interest in science and poetry?

Growing up in the rural community of East Liberty, Michigan, with farmers as neighbours (and dairy farmers in our family), nature became my inescapable companion. With no light pollution, the stars presented a brilliant vista on clear nights. With fields surrounding us, fossils were unearthed with every seasonal ploughing. I attended a one-room school with 35 students, grades one through six, so was exposed to literature and science lessons above my grade level from my first school year. My father was not a farmer, however; he started as a tool & die maker in the auto industry, working his way up to be an assembly line troubleshooter, flying out of town for inspection visits to various plants around the Midwest. So new technologies became his constant dinnertime topic. My mother taught dramatics and had me up in front of audiences reciting poetry from childhood. My earliest love for poetry grew through sound and vocalisation, absorbing the magic of visual imagery later as I matured. My interest in amateur astronomy crystallised through a near-death experience at age 12, from a ruptured appendix in 1965. After 8 weeks in the hospital, my father surprised me with the gift of a telescope, and we became sky watchers through my high school graduation in 1971. That telescope, a standard Newtonian reflector, makes a cameo appearance in my new collection, Driving into the Dreamtime. It appears, unexpectedly, in my poem “Al Kaline’s Line Drive,” partly a baseball poem, partly a tribute to my father; a poem that moves from Kaline’s pivotal base hit in the 1968 World Series through the lunar landing the following year. Kaline, one of the Detroit Tigers’ Hall of Fame players, took a batting stance at the plate where his elbows and bat formed an angular geometry reminiscent of my telescope’s equatorial mount.

I know that you have edited the work of Radcliffe Squires (in the collection Radcliffe Squires: Selected Poems ‘1950-1985’ published in 2017). What is it about Squires’ work that you think marks him out as a proponent of exploring the liminal spaces between science and poetry?

(James) Radcliffe Squires’ academic degrees at the University of Chicago (MA) and Harvard University (PhD) were in literature, which he coupled with a lifelong immersive interest in Classical Studies. But his knowledge of the history and mythology of the Greco-Roman world formed a backdrop for his keen interest in contemporary science. The breadth and depth of this interest is evidenced not only by poems specifically informed by science (“Museum of Natural History;” “Sunday in the Laboratory;” etc.), but in vividly drawn metaphors in his numerous poems of personal experience. In his second collection, Where the Compass Spins (1955) we find imagery that subtly plays upon aspects of relative motion and time dilation forecast by Einstein’s theories of relativity. In “The Subway Bridge, Charles Station to Kendall,” the subway train emerges from a tunnel tellingly described as a “worm hole.”

“…We are one motion and we see

Another. Then we overtake two flying birds

And at the crisis of the wan parabola

Assume their speed. Thus motion dies…”

The same poem concludes by touching upon the Einsteinian concept of the gravitational bending of light: “Faring with the straightness that curves. The line / Of brightness bending as it nears the sun.” In a later poem, “Rapture of the Deep” (1969), Squires adroitly plays upon the awareness then dawning among cosmologists that the birth of biological life on our planet resulted from heavy elements fused in the cores of ancient stars and ejected in stellar explosions. It is now commonplace to hear the phrase “We are the stuff of star-dust” in television shows such as How the Universe Works. But in the mid-1960s, Squires was exploring radically new and unusual territory for a contemporary poet:

“…You lie where the dense egos of stars

Press the come

Of their beginning into a space

Smaller than your mother’s womb.”

A lifelong gardener, Squires also drew upon his intimate experiences with botany to fashion poems that glide seamlessly from personal to universal associations, such as “Frost Line:” “It’s getting dark in this meadow. / I hardly see those flowers / Whose gray moon-mouths / Nuzzle my legs. But my skin tastes / Their coldness and guesses how their roots / Sink like long white hair / Down through moss to where / Snow-water wets the inch of soil / That millions of deaths / And millions of years / Have made. The hard frost / Is beneath that. I feel it / Under the moss that / So quivers and undulates / I have to balance / Myself by moving in a slow dance. / And I see now that all my life / I’ve been dancing on my grave. / There is nowhere else to dance.”

The alpine landscape of “Frost Line” typified Squires’ poems of the western wilderness, having grown up in Utah where he explored the buttes and plateaus of that arid terrain, followed by years of travel through the high glacial altitudes of Wyoming and Montana. In his later collections, Squires found increasingly interesting ways to infuse his descriptions of those rarified landscapes with the sort of cosmological musings noted earlier. “Ramifications” is a splendid example, as it subtly shifts our field of vision from physical to metaphysical contexts: “Flying very high over Wyoming I see / A plateau I once had crossed / By horse – and thought it then / The least human of lands; / For mere mounds of colourless leavings / Rose from a colourless plain, / All of it looking like dust, but all of it /As hard as tufa…. / But here from the plane’s window I see / It is the most human of lands. / Why, it is made like my hand. / From five mounds, thin / Cross-hatched washes run down / Until they intersect and make / Three riverbeds. / And it is like a leaf, as well. / It is like thought whose / Streams long to intersect / In a valley. / Yes, and I think if we had the eyes to see / The beginnings of all things, / What we’d see would be / Light flowing like rivers / Down mountains of light.”

Is it true that Squires was one of the first creatives to respond to the current climate crisis?

Yes. Squires accepted me for an independent study in poetry when I was a graduate student at the University of Michigan for academic year 1976-77. The independent study format allowed our discussions to become more of a two-way mutual exchange of views than the typical classroom setting. Acid rain was already becoming a public bone of contention between Canada and Michigan’s auto industry. My father had personal stakes in that debate, as an industry employee. But he was also an avid fisherman and had experienced the alarming decline of freshwater fish in our annual August vacations to the Upper Peninsula. Squires had already published multiple poems about animal extinctions and ecology, such as “Extinct Lions,” and “Skull Valley, Utah” (about the mass deaths of sheep on Utah ranches caused by nerve gas released from a nearby Army base). I had tried to author a poem or two myself related to environmental concerns and found it difficult to steer clear of neo-romantic sermonising. It was through those discussions that Squires showed me a poem he had recently written, then still undergoing final revisions, titled “The Garden of Prometheus.” This was a remarkably early expression about global warming and the start of the great glacial melt. The poem personifies a melting glacier (“…the ice giant”), as Prometheus, “…slowly pulling the world with his somber declension.” The Prometheus of classical mythology was punished for stealing fire from sky gods. What mythic figure could better symbolise humanity bringing potential disaster down upon itself by heating our planet through the excessive release of fossil-fuel gasses into the sky? That same year (1977) was, of course, the year Exxon’s internal scientists quietly warned their corporate leadership about fossil fuel emissions, and also the year President Carter set up a climate task force. I’ve always suspected that Squires had a friend or two from his graduate school days in one of those inner circles. The only specific comment I can recall was his observation that he had already heard about (or read about, or experienced) several years of abnormally high glacial melt in places like Glacier National Park. But I realised immediately what a wonderful poem he had composed. When he told me he had received an invitation to read and sound-record his poetry for the Library of Congress that next April (April 18, 1977), I commented that I hoped he would include “The Garden of Prometheus.” And in fact, he did structure his reading so that it would be the climactic final poem of his program (he added a brief poem at the very end in memory of his late wife, Eileen). “The Garden of Prometheus” later also become the concluding poem of his most critically acclaimed published collection, Gardens of the World (LSU Press, 1983).

How was this response received at the time?

It certainly received enthusiastic applause at his April 1977 reading, as any listener can hear in the Library of Congress recording. But even though all six of Squires’ mature collections received glowing praise from prominent critics and poets in major media reviews (from James Dickey in the New York Times to Richard Eberhart in The Kenyon Review; from Dana Gioia in The Hudson Review to David Mason in the Oxford Companion to 20th Century Poetry) his poetry fell mysteriously under the radar for years after his death in 1993, to the point that all six collections were long out of print by the time I had the opportunity to edit the 2017 edition of his Selected Poems. In my Editor’s Introduction (which I struggled to complete as my wife gradually fell ill with what turned out to be a brain tumour) I certainly highlight the ecological concerns and scientific imagery one finds in his body of work. Some readers may feel I stress that aspect of his writing a bit too heavily. But I believe Squires himself would approve. During my last brief visit with him in Ann Arbor, he mentioned his poem titled “Pollution,” at that time either recently completed or submitted (I forget which), and he added the thought that it might be apropos if “Pollution” became his final published poem. It was in fact published in The Iowa Review in April 1992, less than a year before his death in February 1993, though I do not know whether it actually was his final poem to appear in print during his life.

How is your own poetry influenced by science?

Entering the University of Michigan in 1976-77 as a graduate student, I had assembled a collection of my earliest poems, several of which had already appeared in little magazines and an anthology. No aspiring student author in Michigan escapes the allure of UM’s Hopwood Awards program. It’s stellar list of award recipients over the decades includes poets ranging from Robert Hayden to Frank O’Hara, John Ciardi to Jane Kenyon, X. J. Kennedy to Marge Piercy (and not to forget playwright Arthur Miller). So the Hopwood Room was one of my first stops in Ann Arbor. I learned that to qualify for the annual contest I first needed to submit my manuscript to one of the University’s resident poets. I had heard Squires give a bookstore reading in 1971, while I was still a high school senior, and had never forgotten it. My independent study began with informal discussions in the middle of Fall Term, and then became official through Winter Term. I then entered my manuscript, North of the Sky (under a pseudonym, as with all Hopwood Award entries), and months later was delighted to learn I’d not only received an award but had won the top award that year in the “major poetry” category. The encouraging written comments by judge Laurence Lieberman helped shape my work for quite a while beyond that year.

Scientific interests found their way into my poetry rather gradually, though certainly inspired by Squires’ examples. In the late 1980s, while teaching the Evening Poetry Workshop at Duke University, my poems that attracted the most favourable attention happened to be “Fossils” and “On Viewing Comet Halley with My Young Daughter.” The former appeared one of those years in Carolina Quarterly, and both are included in Driving into the Dreamtime. The Comet Halley poem made a return appearance this past summer after many years (rather like a comet itself) when it was selected by the Centre for Public Humanities for national distribution over the Centre’s social media channels. From there, it drew the attention of the Los Angeles-based podcast, A Moment of Your Time, where it is beautifully recited by actress Jenny Curtis along with “On Whitefish Bay.”

When I was interviewed for the 2018 anthology, The Hopwood Poets Revisited: Eighteen Major Award Winners, I was also then asked about my poems exploring the experiential impacts of science and technology. My two poems featured in that book, “Touring a Nuclear Reactor” and “The Geneologists,” are perhaps more typical of my recent work than the Comet Halley poem. The former tells the true story of my father (and I) being invited to tour a Michigan reactor through his industrial technology contacts. Almost unthinkable today, that tour left lasting impressions: “…We stand on a stainless-steel / mezzanine, the pool of perfect water below / from where blue floodlights glow like the sky / of Nepal. We know, in that liquid-crystal abyss / of a dark place, cloistered and devious, / where matter was pitted against itself, where a bit / of the world, contradicted, disappeared, and in its / place appeared the perjurious heart of fire…”

In that interview I quoted emailed comments received from one reader who happens to be a scientist: “I suspect that if poems from our time are still being read a century from now, readers will likely be interested in how our poets and novelists interpreted the tidal wave of technologies sweeping over our culture. I’m betting your poems like “Television,” “Home Movie,” “The Geneologists,” and “Touring a Nuclear Reactor” have a real chance to be among those poems…to me, these poems explore our interactions with those technologies on both perceptual and metaphysical levels.” That scientist prefers to remain anonymous, but during this current year, since Driving into the Dreamtime came out in February, I’ve continued to receive similar comments, including a terrific email from Hans Christian von Baeyer, Chancellor Professor of Physics at the College of William and Mary, who writes that he’s been keeping my book on his bedside reading table, and also noting that: “I think that after the 18th century age of reason, the 19th century romantic rebellion, and the 20th century return of rationality beyond all bounds, the 21st is shaping up to be a corrective era in which reason finds its own limits. In that sense, Don, you are in the vanguard of a new era. My own take on physics, with its emphasis on subjectivity, is another symptom of this swing of the intellectual pendulum.”

In your latest collection Driving into the Dreamtime, a whole suite of poetry is devoted to the observations of different meteor showers. What inspired you to write these?

This 12-poem series, titled “Rumi and the Year of Meteors”, began their extremely long gestation during those years I’ve already mentioned (1965-1971). Four of them were published as limited-edition broadsides in 1978. But the entire sequence only reached completion in 2019, while my wife was recovering from a malignant brain tumor. It happened that a major edition of Rumi’s poetry came out in 1968, translated by A. J. Arberry (Mystical Poems of Rumi), as my amateur astronomy zeal was reaching its zenith. Just as meteors interested me as exotic transient visitors from space, so Rumi’s poems of mystical insight intrigued me as quixotic expressions from beyond the English literary tradition. And Arberry even commented metaphorically about Rumi in his Introduction: “His mind was formed of meteor fragments and the like…” My poems do offer one or two actual quotes from Rumi, but more often, they re-interpret Rumi as a voice inside my own head, echoing in a sort of imaginary internal dialogue. They also weave various patterns between science and mythology. The 7th of the sequence, “Draconids,” gives a nod toward Carl Sagan’s The Dragons of Eden: “Their claws cleave our eyes with afterlives. We see tints / of elementals: green of iron first, but only an instant before / burning blood-red as they shatter against the anvil of air. / I see scales tinged like a serpent’s, glinting along the full / length of reptilian skin. Yet they reappear to feather the / sky like parrots of paradise, emerald to ruby to the lavender light / of a final fire. Rumi smiles at memories of feathered serpents / harrowing fables…” And again, the 4th poem of the sequence, “Capricornids”, considers the possible death of a beloved woman through the lens of the merciless vagaries of evolutionary chance (whereas in myth, Capricorn was the goat that suckled the infant Zeus after his mother, Rhea, saved him from being devoured by his father, Cronos): “When we came to the somnolent city of her heart, / she somehow knew the way in, the orbicular path across / the folded scene where night reshaped itself in the aftermath / of Alpha Capricornids. Were this wilderness we’d expect / the sound of indifferent danger: the predatory jaw, / the star-lit eyes of hunger between trees, the yawp / of something suddenly caught, convulsing in the grasp / of inescapable agape. But how can love allow this, I / asked, and she led me back to that solemn lawn where / children played each day over the unidentified remains of / Darwin’s abandoned games…” A last point of possible interest, during my undergraduate years at Oakland University, north of Detroit, I studied with Joan Rosen, who co-authored a book I’ve always admired: A Moment’s Monument: The Development of the Sonnet. Rosen and Gertrude White (also on OU’s faculty) make a persuasive case, I think, that quite a number of modern poets have continued the sonnet tradition, even while slipping the surly bonds of iambic pentameter and predictable end-line rhyme schemes. The Rumi / Meteors poems constitute my version of a contemporary sonnet sequence, by way of White and Rosen’s redefinition.

Do you think that such poetic observations can be equally as ‘valid’ as scientific observations of the same events?

Your interesting question hinges, I think, on one’s view of “validity.” My Comet Halley poem is not directed at readers seeking an explanation of cometary origins or impacts, and so will not be as valid in that sense as even a rudimentary scientific description. Rather, my poem focuses upon the shared experience of a father and daughter who view the same comet while interpreting it in very different ways. That insight into the jaded reactions of a father approaching middle age contrasted with the freshness of the daughter’s youthful excitement becomes the poem’s “validity.”

One night, among innumerable

ordinary nights that interpreted our dreams,

she and I went out into the dark yard to stare

above the tangle of bare limbs where once or twice

a lifetime, Comet Halley reappears. Upon us both

descended dusk’s colander of stars. But through binoculars

the distant lanes of nebulae drew near and there it flared,

glared back at us—portent of pestilence, the thing kings

feared, the apparition astrologers were killed for.

To me, a sadder omen, emptied of terror by a scientist

On tv, only a dim specimen with shriveled tail. To her:

a shaman’s talisman, a shrunken head hung on silver hair.

This past February I was able to finish a “bookend” to that comet poem, titled “On Driving to the Solar Eclipse with My Granddaughter.” This recalls my actual trip from Charlotte NC to Charleston SC with both daughter and granddaughter to see the 2017 total eclipse. We viewed totality (through a blessed break in the clouds at precisely the right time) from NASA’s balloon-launch site on Sullivan’s Island. As it happens, Sullivan’s Island was the intake port for slave ships arriving from Africa. A museum on that island displays navigation maps showing the curving routes those slave ships followed from Africa to Carolina, and I was suddenly struck by how closely those arcs across the maps resembled the curving track of the solar eclipse’s path of totality across the United States. That imagistic parallel sparked the vision of the entire poem, which shapes and reshapes itself into musings on light and dark, life and death, youth and mortality. Therein lies whatever validity it can claim, as an act of creation flowing from an insight of unexpected recognition. I very seriously doubt that any scientific description of an eclipse in history has managed to convey the eerie similarity between the track of an eclipse’s shadow and the path of a slave ship.

I would add the thought that the frontiers of science appear to be presenting us with increasingly perplexing versions of what we think of as “reality.” I refer, of course, to the oddities that began to appear with Einstein and accelerated with the growth of quantum theory. The sheer strangeness (some might say weirdness) of these insights challenges scientists who try, with mixed success, to communicate their possible meanings to the general public. Consider, for example, that concept often called the “multiverse.” While I’ve personally heard scientists struggle with descriptions of this concept, I think that poets may feel freer to explore innovative descriptions and metaphorical aspects that might feel threatening to scientists who worry about a sort of professional peer-group pressure. In fact, Driving into the Dreamtime tries just this in the last of its four distinctive sections: 1) a series of “driving” poems such as the solar eclipse poem already described, followed by 2) “What Must Arise,” which features poems like “Home Movie,” “Television,” and “The Geneologists.” Next comes 3) the Rumi / Meteors sequence, and finally 4) “Verses from the Multiverse.” Here I offer a series of poems that interrogate aspects of our experienced reality that appear to metaphorically imply a multiverse. Some examples: “Conversations with Kali” was inspired by the independent film AWE, which features characters who in the end all turn out to be multiple personalities of the woman named Kali, who suffers from that strange mental disorder. “Winter Trees Seen Through Library Windows” entertains the notion of the multiverse being like millions of books in a huge library, while the persona looks out from the top floor reading room upon forking tree branches that resemble the “tree diagrams” of theoretical linguistics, representing the common language we use to communicate our individual internal “universes of discourse.” The final poem of the book, “Because Capricorn Falling,” touches on the social taboo of an intimate relationship between a male student and a female professor and concludes with speculation on all the imagined ways such a relationship might end or not end. These possible branching futures return to Borges’ “Library of Babel,” by way of the old notion of a vast assemblage of monkeys typing at typewriters, churning out all possible permutations of texts; thus, ending my book in that “…labyrinthine library / where monkeys type our obituaries before our birth.”

In addition to your work as a poet, you are also Director of Library Services at Belmont Abbey College, where you have written extensively about the Information Commons. Can you explain what this system is in a little more detail and the role that it plays in helping to unite different academic disciplines and schools of thought?

After graduation in Ann Arbor, I left to begin my career in public libraries. Motivated by a sort of “Peace Corps” mentality, I found myself in a rural county in North Carolina’s coastal plain, in a library that administered an adult literacy outreach program. I even attended workshops to become a certified author in Laubach Literacy International—a surprisingly interesting learning experience for a poet, with its goal to publish brief books on topics of interest to working parents but written at a very elementary level of vocabulary and grammar. After that, I directed a county library system within easy driving distance of Chapel Hill and Durham, which helped nudge me into directing the Duke University workshop.

Reaching my forties, I was drawn back to academia, where technology was transforming the library into an entirely new paradigm. One component of that paradigm is the “Information Commons.” In 1997 I was hired by UNC-Charlotte to establish and manage the first instantiation of that concept in North Carolina, and at the time, perhaps the fifth or sixth in the United States (today, there are many hundreds on campuses across the US and Canada, with hundreds more across Europe and the Pacific Rim). It had started with the University of Iowa’s Information Arcade, and in 1994 gained the “Commons” label at the University of Southern California. In 2004, USC held a national conference to celebrate that IC’s tenth anniversary, and I contributed a paper titled “From Information Commons to Learning Commons.” I expanded this into my first book (2006), The Information Commons Handbook, with contributions from Russ Bailey of Providence College and Barbara Tierney of the University of Central Florida.Rather than attempt a definition or even description of the IC / LC paradigm here, I would refer interested readers to my 2011 invited paper published through the Educause Center for Analysis & Research (ECAR).

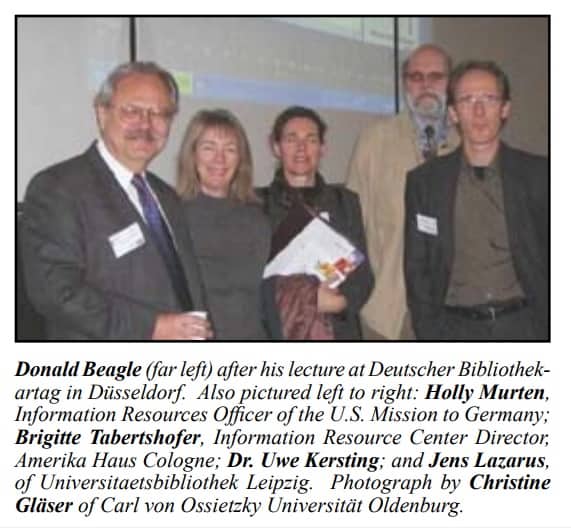

For some discussion of interesting cross-pollination between the Commons and my poetry avocation, I would refer readers to the interview that followed my 2005 invited lecture at Deutscher Bibliothekartag in Düsseldorf, now held by Purdue University’s digital archive.

Are there any other poets who explore the relationship between poetry and science and whose work inspires you?

I think we may be seeing an emergent “school” of modern poets inspired by science, or critically interrogating science. Your own acutely descriptive poems, Sam, seem to me evidence of this, furthered by your editorial work on the exciting journal Consilience. Rather than attempt a necessarily inadequate list of such poets here, let me simply comment on my delight at seeing this year’s National Book Award for Poetry go to the collection, A Treatise on Stars, by Mei-Mei Bersenbrugge. Her book came out in February, about 3 weeks after Driving into the Dreamtime, which I mention because they share elements of cover design (green lettering on vaguely gray graphics, and even similar title fonts) that might have left me worried to have appeared a copycat had their release dates been reversed.

I would not want to lead any scientist to approach her book thinking it attempts an actual “treatise.” It is far more speculative, verging into science fiction of a philosophical bent, but sufficiently grounded in current awareness to reach across various divides. Some imagery in her poem “Pegasus” strongly reminds me of Squires’ “Rapture of the Deep”. I especially enjoy her playful use of extravagantly long lines, contradicting the comfortable tradition of minimalism one can trace back to William Carlos Williams and his red wheelbarrow. Poet Rosanne Coggeshall, who preceded me teaching the poetry workshop at Duke (and who recommended me as her successor when she left to join the Hollins University faculty), once jokingly described that traditional reliance on narrow vertical form as producing “stalactite poems.” There’s nothing wrong per se with stalactite poems (Coggeshall certainly published her share) but perhaps because very short lines have rarely suited my own stylistics, it is refreshing to see a poet try a different extreme. Berssenbrugge’s long lines do not seem to revive Whitman’s oratorical inspiration, however, but strike my ear as sharing clipped sound pattern elements with phrases reminiscent of a digital translation app. Lastly, I want to comment how Berssenbrugge, like Squires, plays with alternate notions of time, of cause and effect. In his final collection, Journeys, Squires offers us a seven-poem sequence of numbered journeys. In Journey #2, we find his typical western desert transformed into a phenomenological landscape: “…We pass, mordant playmate, like pink ghosts / Through the pink ghost of a desert / Where our footprints await us.” In a poem describing her own new collection, Berssenbrugge similarly entangles dimensions of time and consciousness: “Early on, I divined that this book already exists in the future. / After all, I thought of it; it’s a probability somewhere, complete, on a shelf. / My intention is to consult that future edition and create this one, the original, for you.”

Discover more from The Poetry of Science

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

A splendid interview, both from the replies given and the quesions asked. The enlightening details in Beagle’s response, like the insights revealed in his own and Squires’s poems, fulfill a great need we have to penetrate both the world and the consequences of the world we have been making. Salud, my friends.

Thank you Theodore. 😀

Thank you, Theodore, for your incisive observations, and of course for your own wonderful “Afterword” to the Squires’ Selected Poems edition. —Don

Dear Don: This commentary is one of the most fascinating commentaries I have ever read on the topic of Poetry and Science. That you were able to encompass the career and work of Radcliffe Squires as well as your own effective impressions of his versions of the Creation testifies to the united purpose and success of your friendship with Radcliffe. I will read this essayistic series with doubled attention. Speaking of attention, I call your clear eyes and complex interpretations to the publication this month of Beyond Earth’s Edge: The Poetry of Spaceflight from University of Arizona Press. It’s a fascinating anthology, with one of my poems intact. I will write you further on your fascinating commentaries. Surely Radcliffe applauds you from the heavens, as I do from Ann Arbor, your second home.

Thank you, Larry. Like Ted Haddin (of the prior comment), you knew Radcliffe on a personal, professional, and collegial level for far longer than I, so your comments are especially gratifying. And congratulations on having your poem included in Beyond Earth’s Edge: The Poetry of Spaceflight. This anthology strikes me as potentially a watershed publication, helping to blaze a trail for future poets to engage science and technology with the tools of aesthetic insight and humanistic ethos that can take us far beyond the sound bytes of social media and tech terminology.

nice, thank you