Giant clams lie settled

atop distant mountain peaks;

their arid husks supressing

the brackish smell

of ancient waves

that once bathed them

in their shallow,

dampened beds.

Peeling back the layers

with chemical precision,

we read huddled rings

like geological Tarots;

tealeaves strained

by Gaia’s aged sieve.

Calcified shells that

conceal a concerto:

their metronomic lines

mapping the rising pace

of our timeless, lunar waltz.

This poem is inspired by recent research, which has used ancient molluscs to show that 70 million years ago days on Earth used to be about half an hour shorter.

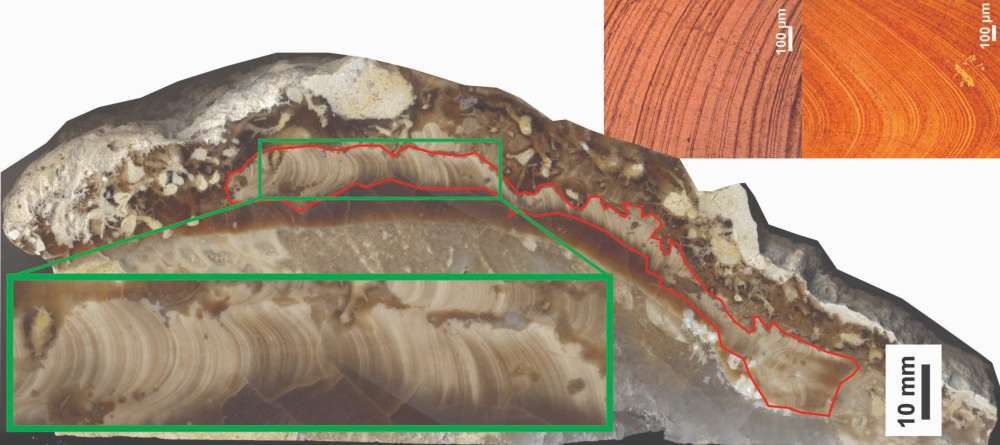

The ancient mollusc, Torreites sanchezi is an extinct form of clam that grew sometime in the Campanian age, approximately 70-80 million years ago. These clams grew incredibly quickly, creating daily growth rings, in a manner analogous to the yearly growth rings that can be seen in trees. By using lasers to sample microscopic slices of shell, these growth rings can be counted and used to determine the number of days in a year, allowing for the length of a day during this geological period to be calculated.

The researchers in this study found 372 daily growth rings per year, demonstrating that the length of day has increased since the Campanian age, as predicted by previous astronomical models; these extra days (372 – 365 = 7), equate to roughly half an hour per day over a one-year-period. Because Earth’s orbit around the Sun does not change, the length of a year has been constant over Earth’s history. However, the number of days within a year has been shortening over time because days have been growing longer, as friction from the ocean tides, caused by the Moon’s gravity, slows the Earth’s rotation. By looking at these ancient clams we are therefore able to get a glimpse into Earth’s history, and better understand its evolving relationship with the Moon.

An audio version of this poem can be heard here: